Continuing my story of the establishment of wool selling in Newcastle, with P A Wright now joining the small group of activists, a new company was formed, the New England, North and Northwest Producers’ Co Ltd, later to be known as NENCO to sell wool and wheat through Newcastle.

The problems facing the new venture were formidable. Lacking capital, it faced entrenched opposition from the Wool Buyers’ Association as well as the Wool Brokers’ Association. Both were protective of the existing system. Neither could see any advantage at all in wool selling at Newcastle, only increased costs.

Wright had expected to gain support in Newcastle, including capital. However, the venture was too far outside the normal interests of the southern city and, in any case, seemed risky. Later Newcastle would adopt wool selling as its own, but for the present this lay far in the future.

Wright and his colleagues adopted a multi-pronged approach to the various barriers facing the venture.

They tried to establish relations with existing buyers and brokers. That move failed and perhaps as well. Had NENCO’s application to join the Brokers’ Association been accepted, the Association could have killed the concept by allocating Newcastle a sales quota that guaranteed commercial failure.

They also sought political and industry support. This did not give them immediate benefits, but provided a degree of protection against possible retaliation from existing interests.

Most importantly, they sought support and capital from major Northern wool growers. Accompanied by W E Tayler, Wright called on Colonel White at Bald Blair. In Wright’s words, White was widely regarded as one of the foremost men in the North. If he came in, the venture would gain immediate credibility.

White was not enthusiastic. To Wright’s dismay, White said that he would not take part; so far as he was concerned, they could sit on their own bottom. Thinking about it, White was to change his mind, to join NENCO as a shareholder and director. Other big graziers joined as well.

While it wasn’t clear at the time, this growing support gave NENCO the commercial edge to succeed. The grower members produced a substantial clip. They were prepared to sell this through Newcastle even if it meant lower prices, taking a lower return now to achieve their longer term objectives.

The first Newcastle sale took place on Thursday 1 November 1928. NENCO’s own premises were not ready, so the wool was displayed at the old Newcastle skating rink, with the auction held at the Church of England’s Tyrell Hall.

That sale was a disappointment. Of the 1,760 bales of wool on offer, only 25 per cent was sold, although 60 per cent was sold later. The scheme’s opponents crowed. It was a failure.

At this point, the support of the bigger growers became critical. They would sell their wool through Newcastle regardless. This was enough to guarantee ultimate success. The rest, as they say, is history.

Note to readers: This post appeared as a column in the Armidale Express Extra on 18 June 2014. I am repeating the columns here with a lag because the columns are not on line outside subscription. You can see all the Belshaw World and History Revisited columns by clicking here for 2009, here for 2010, here for 2011, here for 2012, here for 2013, here for2014.

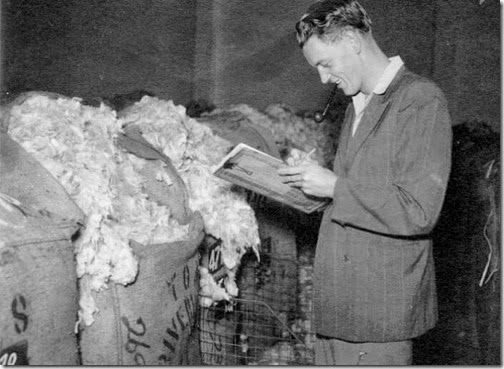

The photo from the Newcastle Regional Library shows a wool classer inspecting wool for sale in 1950.