By December 1920, the new state fire that Victor Thompson had lit in January 1920 may, as Earle Page said, have burnt well, but the new Movement still had to turn that heat into reality.

The events that followed over the next four years are complex, deeply entwined in local, state and Federal politics. I can only sketch some of the key features.

The embryo movement formed at the Glen Innes convention in August 1920 was transformed into a full scale movement that, by the end of 1921, had 200 leagues across the North.

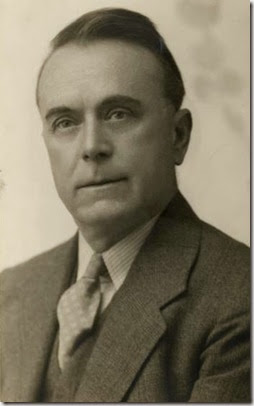

Recognising the need for national support, the Northern leadership took the subdivision cause onto the road. They reached out into Queensland where support for separation was already strong in Central and Northern Queensland. Here they were joined by Labor politician and later Prime Minister Frank Forde (photo) who, as member  for Rockhampton in the State Parliament, had been actively promoting the subdivision of Queensland.

for Rockhampton in the State Parliament, had been actively promoting the subdivision of Queensland.

In Southern New South Wales, the Northern campaigners were successful in creating an active movement seeking statehood for the Riverina. Then, in July 1922, a national new state conference was held at Albury. Convened jointly by the Riverina and Northern Movements, the conference aimed to coordinate the activities of the various separation movements that had sprung up as a result of the Northerners’ campaign.

Attended by representatives including seven parliamentarians from twelve organisations covering NSW, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia, it formed an All Australian New States Movement with Earle Page as President, Victor Thompson as secretary.

Also in July 1922, Frank Forde successfully moved a motion in the Queensland Parliament calling for constitutional change to allow the formation of new states, while Drummond moved a motion in the NSW Parliament calling for immediate action to create a new state in Northern New South Wales.

This motion was opposed by the Labor opposition who argued that any subdivision should take place only in the context of an overall revision of the Federal Constitution that would strengthen Federal powers and replace the states with provinces.

The Government’s position was more complicated. The Premier conceded that new states were inevitable in the longer term, but also felt that it was simply unreasonable to expect members to agree to a motion that would mean loss of territory for NSW. An amendment was therefore moved and passed asking the Federal Government to convene a convention to consider the question, thus neatly shelving the issue.

The Federal elections of December 1922 saw the election of new staters P P Abbott to the Senate, Victor Thompson to the House of Representatives as member for New England. It also saw the emergence of the Country Party in a position of balance of power.

Page, now Country Party Leader, was determined to assert country interests. He demanded that the new Government be a joint one, a coalition of equals. The result was the formation of the Bruce-Page ministry.

The door now seemed open to real action to force self-government for New England. It wasn’t to be as easy as that.

Note to readers: This post appeared as a column in the Armidale Express Extra on 20 August 2014, the next in a series telling the story of the Northern or New England self-government moment. I am repeating the columns here with a lag because they are not on line outside subscription. You can see all the Belshaw World and History Revisited columns by clicking here for 2009, here for 2010, here for 2011, here for 2012, here for 2013, here for 2014.

If you want to follow the story of the Northern or New England self-government movement, this is the entry post for the whole series