My last column outlined some of the economic and political events leading into the Great Depression. In the economic and political turmoil of 1930 and 1932 the very fabric of NSW life began to collapse. Many blamed the existing politicians and political parties for the problems and condemned them, calling for new approaches.

New political movements now mushroomed on the right and left of politics. Formed in February 1931, the All for Australia League claimed a membership of 130,000 by the end of June. The Unemployed Workers Movement formed in April 1930 claimed a membership of 31,00o by the middle of 1931. A strong undercurrent of fear ran beneath this political activity.

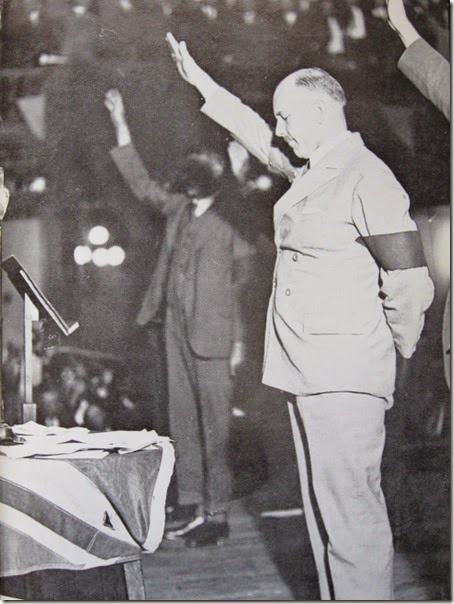

As the fear of revolution spread, private citizens began to arm, forming unofficial paramilitary organisations. On 18 February 1931, just nine days after Lang announced the Lang Plan, a private meeting of eight men at the Imperial Services Club in Sydney decided to form the New Guard. In less than a year, the Guard had grown to 87,000 men.

The Guard courted publicity, and this has given it a faintly comic air. However, it was arguably very dangerous; its strident rhetoric was associated with a well organised military structure, largely in Sydney, that might have allowed it to seize power.

Less flamboyant than the New Guard was the shadowy organisation known as the “Movement” to its members. Formed in November 1930 the Movement, later derisively called the Old Guard by its New Guard rivals, aimed to build up a disciplined force of 9,000 men who would only be called out in the event of a situation beyond police control.

While the strength of para-military forces in the North is difficult to gauge, it is clear that units were formed. However, although there appear to have been small New Guard branches at Lismore and Newcastle, the great majority of Northern groups were almost certainly independent or associated in some way with the Old Guard rather than the more efficient and extreme New Guard.

It is also reasonably clear that the Northern separatist leadership had at least had some knowledge of, if not connections with, the Old Guard. This is hardly surprising, given the number of ex-military officers connected in some way with the Northern New State Movement, for these formed the core of the Old Guard.

Nevertheless, whatever the strength or indeed affiliations of Northern para-military groups, their very existence was an important influence in the increasingly confused political climate of 1931 and early 1932.

In these circumstances, Page’s 17 February 1931 Glenreagh speech calling on the North to secede was not just a dramatic gesture. It was very close to a formal call to arms, a call for revolution.

Note to readers: This post appeared as a column in the Armidale Express Extra on 12 November 2014. I am repeating the columns here with a lag because they are not on line outside subscription. You can see all the Belshaw World and History Revisited columns by clicking here for 2009, here for 2010, here for 2011, here for 2012, here for 2013, here for 2014.

If you want to follow the story of the Northern or New England self-government movement, this is the entry post for the whole series

No comments:

Post a Comment