Robert Dawson was the first Chief Agent of Australia’s first really large public company, the Australian Agricultural Company[i]. If he had not clashed with a Macarthur family determined to feather its own interests, he would not have been first suspended in April 1828, dismissed in January 1829. Had that not happened, he might not have written the two books he did, some of the first writing connected with New England.

Born in 1782 at Great Bentley, Essex, Dawson was educated at Dr Lindsay's Grove Hall School near Bow, returning to Essex to farm the family estate. In 1811 he married Anne Taylor. Ten years later, an agricultural depression forced him to Berkshire where he managed Becket, Viscount Barrington's estate. That move would affect the later naming of New England features including Barrington, the Barrington River and Barrington Tops.

In December 1824 an old school friend, John Macarthur junior, persuaded him to accept the post of chief agent in New South Wales for the newly formed Australian Agricultural Co. His key role was to establish and manage a new pastoral business based on a land grant of 1,000,000 acres (404,609 ha). In carrying out this role, he would be subject to a committee resident in NSW. This committee was entrusted by the directors in England with 'extensive discretionary powers,. Dawson was advised to accept their advice at all times.

On the surface, this made sense. The directors in England could hardly directly govern such a distant operation. They needed an on-ground supervising body made up of local experts. However, the committee was dominated by members of the Macarthur family, and this would case trouble.

Dawson had to organise many things. After buying stock in France, Saxony and Spain and recruiting workers, The Australian Agricultural Co party sailed for Sydney in the ships York and Brothers. On the trip, Dawson was assisted by his nephew John Dawson, then nineteen. In November 1825, the small convoy reached Sydney. On board were a party of 15 men, 14 women, 40 children, more than 600 sheep, 12 cattle and 7 horses.

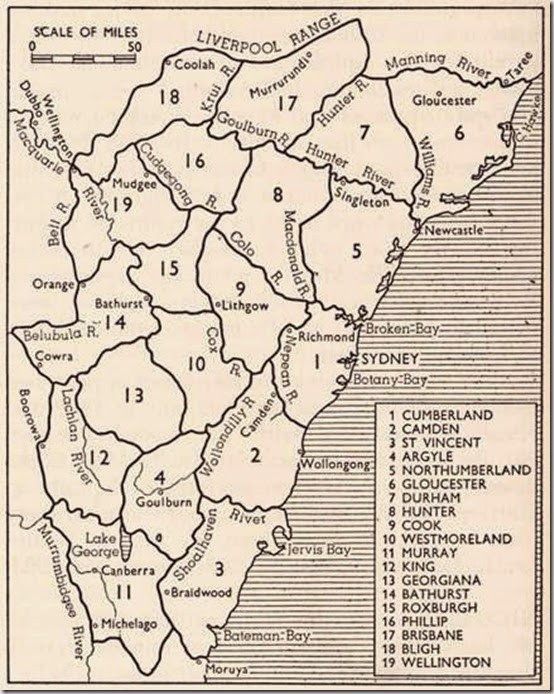

Meantime, the local committee had been considered the three alternatives for the land grant suggested by Surveyor-General John Oxley. They concluded that the area between Port Stephens and the Manning River was most suitable for the company's activities, although this was not Oxley’s preferred site. After inspecting the area in January 1826, Dawson accepted this advice. He recommended that the whole establishment should be moved there as soon as possible. Later, Dawson would be criticised for not checking the other sites. Objectively, it is hard to see what else he could have done.

Dawson moved rapidly. By June 1826 headquarters had been established at Carrington on Port Stephens; by 1827 much land had been cleared and spacious stores and workshops erected. Dawson had already recognised that the humid coastal country was not suitable for sheep and had begun to move stock inland. His efforts attracted praise, including from James Macarthur who in May 1827 spoke highly of Dawson’s management and the progress being made.

Trouble now broke out. Dawson, concerned at the way the Company was being forced to buy old and diseased sheep from the local committee’s flocks, refused to buy more. 'I was no longer disposed”, he wrote to James Macarthur in June 1827, to make the Company Grant a burial ground for all the old sheep in the colony'.

James Macarthur moved against him. On 27 December 1827 he paid another to Carrington. This time, his report castigated Dawson for mismanagement and extravagance. He was accused of bad management and insubordination, of taking up land on the north bank of the Manning River and running his own flocks on it, of using the company's resources in exploring and settling it. John Macarthur stated: 'The concern cannot prosper because the Company's servants are only solicitous for their own interests', In April 1828 Dawson was suspended by the local committee and, on James Macarthur's report to the court of directors in London, was dismissed in January 1829.

Dawson fought back. Now in London, he published his Statement of the Services of Mr Dawson, as Chief Agent of the Australian Agricultural Company[ii]. Apart from providing details of the early days of a significant part of New England’s history, it is the first written record of corporate infighting in Australian history.

The following year, Dawson published a second book, The Present State of Australia; a Description of the Country, its Advantages and Prospects with Reference to Emigration: and a Particular Account of its Aboriginal Inhabitants[iii]. It was this book that really left his longer term mark. Nor only was it in part the story of the establishment of the Australian Agricultural Company, but it also became a fundamental source book on New England’s Aboriginal peoples. Dawson liked them, respected them and employed them.

Dawson’s efforts to achieve justice slowly had an effect. In 1836, after repeated representations to the Colonial Office, he was given land in New South Wales in recompense for the grant he had sought unsuccessfully from Sir Ralph Darling in 1828 even though such grants were now forbidden by law. He returned to New South Wales with his second wife in 1839 to superintend his estate, Goorangoola, on the upper Hunter: he also acquired a 100-acre (40 ha) grant at Little Redhead, near Newcastle. Soon after his return he was again appointed magistrate for the area. One of his last recorded actions in New South Wales was to advise on the Botany Bay water supply scheme for Sydney.

Dawson returned to England in 1862, dying in 1866 and was buried at Greenwich. He was survived by two sons and one daughter of his first marriage and by one son of his second. The elder son of his first marriage, Robert Barrington, became well known as a civil servant and pastoralist. In the end, even the directors of the company had some awareness of the wrong done. 'The misconduct of Mr. Dawson is far exceeded in culpability by that of the Committee whose orders he was to obey', the directors recorded.

[i] Material in this piece is drawn especially from E. Flowers, 'Dawson, Robert (1782–1866)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dawson-robert-1969/text2379, published in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 17 February 2014.

[ii] Statement of the Services of Mr Dawson, as Chief Agent of the Australian Agricultural Company. (London, 1829), accessed on-line. http://digital.slv.vic.gov.au/view/action/singleViewer.do?dvs=1392619628144~191&locale=en_US&metadata_object_ratio=10&show_metadata=true&preferred_usage_type=VIEW_MAIN&frameId=1&usePid1=true&usePid2=true 17 February 2014

[iii] The Present State of Australia; a Description of the Country, its Advantages and Prospects with Reference to Emigration: and a Particular Account of its Aboriginal Inhabitants, (London, 1830). Accessed online - . http://books.google.com.au/books?id=6swNAAAAQAAJ – 17 February 2014