“A number of Movement leaders and especially Drummond would give evidence, articulating constitutional issues”

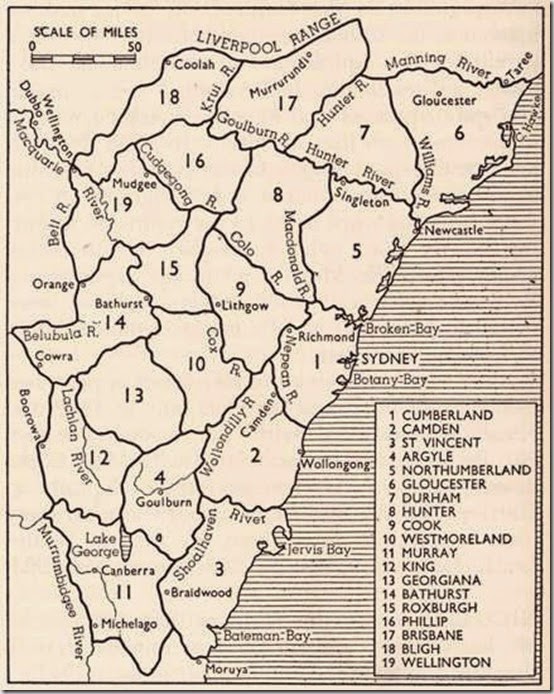

My next columns return to the story of New England’s fight for self-government, this time looking at the sometimes tumultuous events of the Depression years. As happened during the 1920s, large scale separatist agitation developed. This led to another Royal Commission, the Nicholas Royal Commission. Then, again as happened in the 1920s, the New State Movement effectively collapsed, exhausted by its efforts.

In May 1927, Victor Thompson had convened a meeting of the Northern New State Executive. In a sombre report, Thompson outlined the Movement’s problems.

The new state issue, he told delegates, was confined almost wholly to the North. Even there, the people were too divided in their political allegiances to become solid on the issue. Neither the Labor nor National Parties had any policies towards the establishment of a larger measure of self-government in any part of NSW, while the Country Party could not stake its existence upon a new state for the North. In all, there was no chance of action at state level.

Accepting Thompson’s analysis, the Executive decided to concentrate on seeking amendment of the Federal Constitution. It also decided to convene another convention at Armidale to examine proposals for the extension of local government within the existing state in accordance with the recommendations of the Cohen Commission. Given the Movement’s previous opposition to such councils, this was an act of despair.

As planning got underway, the Movement achieved one of its long-sought breakthroughs with the appointment by the Bruce-Page Government in August 1927 of a Royal Commission (the Peden Commission) to inquire into the Australian constitution.

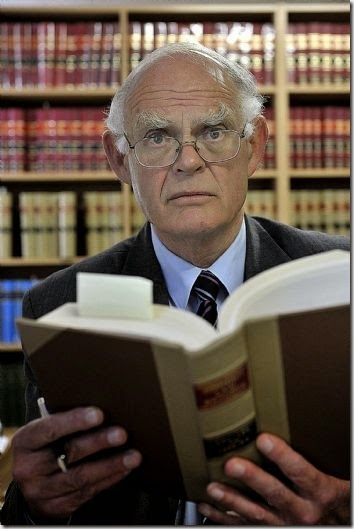

A number of Movement leaders and especially Drummond would give evidence, a rticulating constitutional issues that would be of continuing importance. There is not room in this series to look at the detail of those issues. However, it is worth noting the role that Northern new state supporters have played in trying to force debate on constitutional issues from the 1920s to, most recently, the arguments of the late Bryan Pape (photo).

rticulating constitutional issues that would be of continuing importance. There is not room in this series to look at the detail of those issues. However, it is worth noting the role that Northern new state supporters have played in trying to force debate on constitutional issues from the 1920s to, most recently, the arguments of the late Bryan Pape (photo).

It would be September 1929 before the Peden Commission reported. Meantime, the Movement went ahead with its plans for the third Armidale convention, although at first there was little enthusiasm. Despite this, the Movement planned the convention carefully.

A detailed plan for regional councils was prepared and widely circulated. The Northern press played its now usual role in publicising the issues. The end result was that the convention held over three days in April 1929 was well attended. There were thirteen parliamentarians present, while delegates came from sixty-eight towns.

In putting forward his regional council proposal, Victor Thompson was probably reflecting local opinion. Earle Page would have none of it. In a fiery speech he appealed to delegates not ‘to touch this unclean thing’ and won the day. The convention decided to continue the press towards self-government.

The convention had strengthened the Movement. Now events would bring the self-government cause back to centre stage.

Note to readers: This post appeared as a column in the Armidale Express Extra on 22 October 2014. I am repeating the columns here with a lag because they are not on line outside subscription. You can see all the Belshaw World and History Revisited columns by clicking here for 2009, here for 2010, here for 2011, here for 2012, here for 2013, here for 2014.

If you want to follow the story of the Northern or New England self-government movement, this is the entry post for the whole series