One of the things that fascinates me wearing my historian’s hat is the way that technology affects our view of the world. Last week, I talked about the bicycle. This week I want to talk about feet and hooves.

We live in an accelerating world. Our world has expanded, but also contracted. The intensity of immediate place has been lost.

This has practical implications for places like Armidale that have been sidelined by time because they are outside the main transport nets. However, for now, my interest is more basic.

As a rough starting point to our discussion, human beings on a long distance ramble walk at around two and a half miles (a bit over 4k) per hour. At this speed, they can go and go.

A Roman Army was expected to be able to march in full kit perhaps 24-32k per day and then set up camp. Alexander the Great’s army was estimated to occupy 26k of road without baggage animals. This meant that the leading elements would be setting up camp before the previous camp had emptied fully!

Now introduce hooves. Surely things went faster? Well, not necessarily.

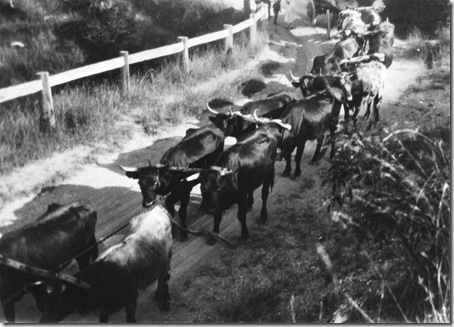

Travelling with stock, speed is determined by the speed of the animal. From my limited experience with sheep, I haven't travelled with cattle, travel becomes a slow amble, less than a normal walking pace. Say eight hours to drove from Uralla to Armidale. You may have horses, but your speed is determined by the stock.

A bullock dray is not much faster. You now have the capacity to carry heavier loads, but the pace is slow.  There are a number of recorded stories of women and children leaving the dray on foot and arriving home hours before it. Just walking like them, you might get to Uralla in five hours.

There are a number of recorded stories of women and children leaving the dray on foot and arriving home hours before it. Just walking like them, you might get to Uralla in five hours.

Say you have a horse. The fastest sustainable speed for a horse is a trot, a speed that can be maintained for an extended period. My research suggests that this equals about 8 mph (13 km/h). Now, speeding, you can get to Uralla in a bit under two hours. Presumably roughly the same speed equation would hold for something like a sulky.

Growing up in Armidale, I was probably closer to this old world than modern Armidale kids or indeed their parents.

We travelled by foot or bike. When we went by car along the dirt roads to a picnic at, say, the Gwydir River, we knew the exact patterns of country, the precise point at which the Tablelands suddenly turned to the Western slopes. It was a very particular peak on the road.

When I first returned to history, I was absorbed in the present. I couldn’t properly understand some of things I read. They seemed strange, odd. Then I realised that I had to put myself back into that past, into a world marked by the vast presence of the immediate locality. My writing is the better for it.

Note to readers: This post appeared as a column in the Armidale Express Extra on 21 August 2013. I am repeating the columns here with a lag because the columns are not on line outside subscription. You can see all the Belshaw World and History Revisited columns by clicking here for 2009, here for 2010, here for 2011, here for 2012, here for 2013. The photo comes from John Caling.