While Will's writing has obviously been important, there is a problem from the particular perspective of this blog, one that I have referred to before. I put part of the problem this way in a post I wrote on 17 September 2010, New England's Aboriginal artists:

This blog (Will's blog) is an education on Aboriginal art and beyond into Aboriginal culture and history. However, it does have one weakness from my perspective, its remote area focus.The problem extends beyond this. One of the recurring themes in my writing on Aboriginal issues has been our failure to recognise diversity among Australia's Aboriginal people. This, I suggested, distorted perception, thought and policy.

While I am interested in Aboriginal art in a general sense, I also want to know more about Aboriginal art connected with New England. Like many other aspects of New England life, this is actually quite hard to do because the information is not readily available.

At this point I don't want to revisit my past arguments, although I will need to do so at some point. Instead, I want to look at some of the historiographical issues raised by any consideration of social change among New England's Aborigines in the period 1950-2000. In so doing, I also hope to interest you in this part of New England's story.

The 1965 Freedom Ride

Influenced by the civil rights struggle in the United States, in February 1965 a group of University of Sydney students organised a bus tour of western and coastal New South Wales towns:

Their purpose was threefold. The students planned to draw public attention to the poor state of Aboriginal health, education and housing. They hoped to point out and help to lessen the socially discriminatory barriers which existed between Aboriginal and white residents. And they also wished to encourage and support Aboriginal people themselves to resistThis photo shows students confronting locals and police at Moree.discrimination.

The ride has achieved iconic status. Now what you won't get from the historical material because New England doesn't exist in a formal sense is that nearly all the towns visited were in New England. The phrase "western and coastal NSW towns" is actually misleading because it denies geographic specificity. As a consequence, you also won't get any feel for what went before or what came afterwards beyond the very broad-brush story of changing Australian attitudes and policies towards its Aboriginal peoples.

Importance of Aboriginal New England

While the New England Tablelands itself had a relatively small Aboriginal population, the surrounding river valleys were ecologically rich. Reflecting this, the Aboriginal population was high. As a result, at the first census in 1971 recording the Aboriginal population, the number of NSW residents self-reporting as Aboriginal were heavily concentrated in New England.

The total number of self-identified Aborigines was quite low, 23,101 in all. Of this group, 12,760 (55%) lived in New England. The proportion is quite startling, more so if the unknown but quite high proportion of New England ancestry Aboriginal people living in the Sydney metropolitan area is included. This means that the story of New England's Aboriginal peoples is actually quite important. Indeed, and I accept that I have biases, if you don't understand their story, then it is very hard to understand the total story.

Application of Universal Frames

One of the most complicated things in understanding the story of Aboriginal Australia after the arrival of the Europeans is to understand the way in which European perceptions affected the country's Aboriginal peoples. This affects every aspect of both history and the writing of history.

At evidence level, the problems involved in using ethnohistorical evidence are generally well understood, partially as a consequence of researchers from the University of New England. This was the first University in Australia to look in detail at the ethnohistorical

material across a broad but geographically related area.

material across a broad but geographically related area.The position at a cultural and policy level is less well understood. This photo shows an Aboriginal Ball at Moree.

From the beginning of European settlement, the various governments in the new colonies had to work out just how to respond to the local inhabitants.

The tragedy is that some of the greatest damage, and this remains true today, was done by the best intentioned. They formed general views, universals if you like, and then applied them holus-bolus.

The results were disastrous because policy changes always come with a lag.

The first attempts to "civilise" and "educate" Aboriginal people in NSW failed because of the vast incomprehension between European views and the realities of traditional Aboriginal life. There was then a gap.

When interest resumed, the Aboriginal people had moved on. With traditional life destroyed, many Aboriginal parents had accepted that their kids needed education, must fit in to the new society. Now, however, they had to deal with a resumption of official interest in Aboriginal welfare.

The tragedy was that views held by European benefactors and community activists, by officials, had been formed by experiences and conclusions formed all those years before. If nothing had been done, if those parents who wanted it had been allowed to enrol their kids in the new public school system letting the rest find their way, the the Aborigines would have been far better off.

Yes there was prejudice that would have affected some, but people would still have broken through. In NSW it would be the 1960s before the first Aboriginal person achieved a university degree. A policy of benign neglect would have achieved this result years earlier.

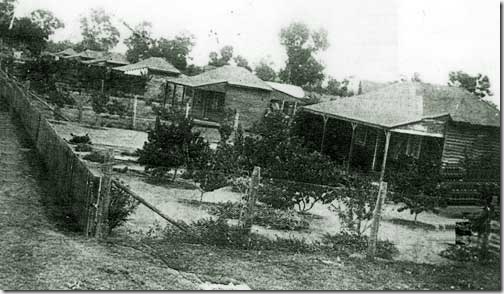

The next photo shows mission houses built at Pilliga not far from Moree.

With renewed interest, the NSW Government moved to introduce a series of measures intended to "protect" the Aborigines. Now we come to the world of missions, reserves and fringe dwellers, of a separate Aboriginal education system whose central assumption was that Aboriginal peoples could not hack it in the conventional education system. We also come, eventually, to the stolen generation.

Importance of Northern Australia

In their 2007 book Beyond Humbug: Transforming government engagement with indigenous Australia (Seaview Press, South Australia, 2007), Michael C Dillon and Neil D Westbury pointed to a number of problems with the policies of various Governments towards Australia's indigenous people.

The book argued, correctly to my mind, that one problem had been a lack of rigour in policy making. It also argued, again correctly to my mind, that a second problem lay in the failure to recognise Indigenous difference, leading to a one size fits all approach.

All this said, the flaw in the book lay in the way that the authors, having made these points, actually generalised from Northern Territory experience. The NT is only a small part of Indigenous Australia.

In that same year, on 22 June, then PM Howard and Minister Brough announced that Australian Government was taking over direct control of the Northern Territory's Aboriginal lands and the communities on them. The intervention was driven by conditions in specific Aboriginal communities, but led to policy changes that affected first all Australia's Aboriginal peoples and then the broader community.

This is outside my period, but in a sense book-ends some of the discussion.

From Federation, there were discussions among Australian Governments a

bout the development of common approaches to Aboriginal affairs. These discussions were strongly influenced by conditions in areas that had large Aboriginal populations still living in traditional ways. This created peculiar difficulties in NSW.

Many in NSW believed, incorrectly, that traditional Aboriginal life had been extinguished. I say incorrectly because we now know that elements of that life and its traditions continued. Yet it is also true that the issues and conditions facing those of Aboriginal descent in NSW were different from those in Northern Australia. By the 1880s, an increasing number of Aboriginal parents or parents of Aboriginal descent wanted just the same things as other parents: work, a home and an education for their kids.

The problem that arose is that those of Aboriginal descent in NSW faced a denial of traditional life on one side, the application of policy approaches based on traditional stereotypes on the other, policy approaches that impeded social progress and change. This second was effectively reinforced by the evolving national conversation, as well as on-ground prejudices.

Because New England had such a large Aboriginal population, because that population was visible in a way not seen in Sydney, issues of race, prejudice and stereotypes played out on the ground. New England was both a source of change and of resistance to change.

The students who visited Moree in 1965 found a town that was marked by prejudice and divide. The students then left. Their visit did have local effects. However, it was the town itself and its people who had to adjust, to work things out in their own way.

Today, 22% of the population of Moree Plains Shire is Aboriginal. Prejudice still exists, but Moree is a very different town to the one the students visited.

Changing Universal Frames

By the time the students visited Moree, fundamental change was well underway. Riven by contradictions, NSW public policy towards the Aborigines had begun to shift and shift quite quickly.

Education is one theme that I intend to focus on, in part because my grandfather was NSW Minister for Education for much of the period from 1928 to 1941, in part because education was just so important.

David Drummond himself captures all the pressures and contradictions built into official policy at a time of change. His attempt to make sense of a policy, to create structure, through the articulation of the concept of a child race, foundered not just on the fact that the policy made no sense to begin with, but also on practical electoral issues.

Faced by Aboriginal parents from the Woolbrook school, some of his electors, demanding an education for their children in the public school system, he could not deny them even though White parents were opposed.

Drummond's case is interesting, but more important is the way that official policies denied Aboriginal children a first class education over so many generations. By the time official policies really changed, generational disadvantage had been further built in.

On 27 May 1967, two years after the student visit to Moree, the Australian people overwhelmingly approved an amendment to the constitution giving the Commonwealth, among other things, the power to make laws specifically in relation to Aboriginal people. In many ways, this constitutional referendum marked a symbolic rather than substantive change, but symbolism is important.

Between 1950 and 1967 there had been significant change and not just in education. One marker here is the growth in interest in Aboriginal culture and history. Here the University of New England both reflected national trends and played an important role in the work itself. It also provided a very specific regional focus, another element in the story.

In some ways, the interest in Aboriginal culture and history seems to have peaked in the early 1970s for reasons that are still unclear to me.

This is not meant to be an absolute statement. Interest in particular aspects continued, such as the long-running boom in Aboriginal art. However, looking at the historical writing in particular, a focus on the Aborigines as Aborigines seems to have been replaced by a focus on black-white relations and on the Aborigines as victims.

I am making this statement cautiously because it is subject to correction. What, I think, is more certain is that there was a decline in interest in the specifically local or regional aspects of the Aboriginal story.

This trend coincided with changes in public policy approaches. Of especial importance here was the emergence of the idea of Aboriginal self-determination, along with new approaches to land-rights. Again, we have the development of new absolutes, new universals, that played themselves out at national, state and regional levels.

I have a lot of work to do here to really understand what happened. I have opinions, but they have to be tested against the evidence.

To state my personal view up-front, and as had happened so many times before, I feel that the new approaches worked to conceal and submerge diversity. Entire new political and social structures were created that, of themselves, came to work against real change. Yet the picture is so complicated that I remain uncertain.

Let me take an example.

The NSW Aboriginal Land Council states on its web site:

It is a common misconception that the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council was established as a direct result of the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NSW) in 1983.I am sure that that's true. As NSWALC notes, a non-statutory NSW Aboriginal Land Council was established in 1977 as a specialist Aboriginal lobby on land rights. It was formed when over 200 Aboriginal community representatives and individuals met for three days at the Black Theatre in Redfern to discuss land rights.

Yet while true, the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NSW) is of critical importance because it set a formal legal framework that, with amendments, continues to this day. It is also a framework with built in contradictions and tensions that also continue to be important.

Aboriginal Responses to European Frames

No human being can be oblivious to the views held by others. People respond at both individual and group levels. We have already seen this is some of my earlier discussion.

One aspect of the process is called mirroring, the way in which a minority group comes to respond to and to a degree reflect the views of the dominant majority.

The process is a complicated one. Simply put, every change in social and official attitudes towards Australia's Aboriginal peoples has been reflected in changes within the Aboriginal community in both structures and attitudes. This is as true in New England as it is in the broader nation. It was also as true in 1788 as it is today.

Some Aboriginal people simply escaped, merging into the broader community. This was encouraged by official policies, more so by the problems involved in being Aboriginal. We have no idea of the number involved, although it seems to have been high.

One anecdotal measure of this is the number of Australians who are now willing to recognise that they have some element of Aboriginal ancestry. A second measure is provided by a comparison of the 1971 NSW census figure of 23,301 as compared to the 138,506 number reported in the 2006 census.

That's a very big increase, far greater than can be explained by the higher Aboriginal birthrate. Part of the increase comes from better reporting. A bigger proportion comes from an increase in the number of people willing to recognise themselves as Aboriginal. One side-effect has been a decline in the proportion of Aboriginal people living in New England.

This leaves open the question as to why New England should have had such a high figure in the first place. Part of the reason lies in higher numbers to begin with. But part also lies, I think, in the fact that New England had retained a large number of people who were identifiably Aboriginal and who lived in specifically Aboriginal communities.

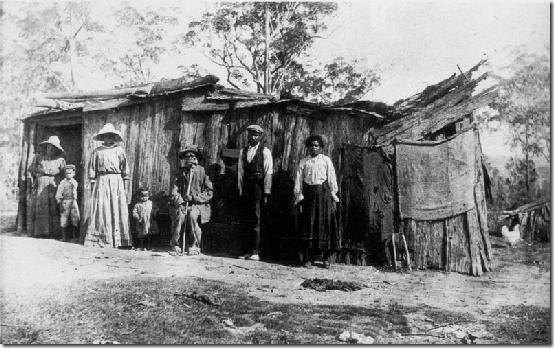

This photo is of an Aboriginal family living on an island in the Bellinger River near Urunga. Similar photos can be replicated across New England.

The high number of identifiable Aboriginal people living together facilitated elements of cultural retention including language, but also meant that New England's Aborigines were strongly affected by changing attitudes and policies. As a modern example, 61 of the 119 NSW Aboriginal Land Councils are to be found in New England, spread across no less than five NSW Aboriginal Land Council regions.

I am still working through the way in changing policies and structures over the last three decades of the twentieth century affected New England Aboriginal life and perceptions. The picture is a complicated one, further complicated by the fact that I necessarily write as an outsider.

Islands of Poverty

One of the most difficult things to deal with is the way in which previous approaches have created islands of poverty. Further, those islands are quite visible in New England because of the relative size and concentration of the Aboriginal population.

I am writing a history, not a public policy analysis, although the two are obviously connected. With some manipulation, census data does provide something of a snap-shot across New England at the end of the period. What is less clear to me is the extent to which poverty has shifted in both absolute and relative terms.

My hypothesis is that Aboriginal living standards improved over the 1950s and 1960s, but then went into reverse as a consequence of broader structural change and associated changes in the world of work that reduced the availability of unskilled and semi-skilled work. This especially affected Aboriginal people because their education was generally poorer.

This links to another factor, internal migration. For historical and cultural reasons, the Aboriginal population has always been mobile. Today, that population is noticeably more mobile than the NSW population as a whole. However, the patterns of mobility are different. This has significant affects on Aboriginal demography and on the structure of Aboriginal life, as well as on the overall structure of the New England population.

In some New England centres, the Aboriginal proportion of the population has increased over the period we are talking about because of emigration especially of the non-Aboriginal young. In other New England centres, the Aboriginal proportion of the population has increased because of in-migration by Aboriginal people. In still other areas, the once relatively large Aboriginal populations have been increasingly swamped by in-migration of non-Aboriginal people.

Concluding Trends

I have barely scratched the surface in this preliminary discussion. However, I want to finish by just mentioning a number of other changes:

- One big change has been a shift in the role and attitudes of local Government towards a constant recognition of Aboriginal interests. While this is a broader trend, it has special importance in New England with its higher Aboriginal populations. It is not, I think, a coincidence that the 1983 election of Pat Dixon to Armidale City Council was the first time that an Aboriginal person had been elected to a local council in NSW.

- A second and very important change, one that deserves a full post in its own right to extend my discussion in earlier posts, has been the rise of Aboriginal consciousness. This has played out across many areas of life, including writing, painting and the Aboriginal Language Revival Movement. Again, New England's bigger Aboriginal population has had an impact: New England languages are central to language revival; one of the best know national Aboriginal papers (the Koori Mail) is based in New England; while writers and painters with New England connections are also prominent.

- Finally and perhaps more problematically, there has been the rise of Aboriginal specific jobs.