I started my last column by posing a question: just how did Armidale get not just one but two higher educational institutions in the space of ten years? I spoke of the way that the combination of the re-emerged New State Movement with the formation of the Country Party helped set the ground. But I also said that beyond these factors was the simple rivalry of two educators with very different views about teacher training.

The announcement in December 1927 that a Teacher’s College was to be established in Armidale was not welcomed by all. Newly appointed Principal CB Newling later recalled that the Armidale proposal met active hostility within the Sydney press, among city interests and within the NSW Department of Public Instruction. Importantly, potential students fearful of the likely standards of the new college were reluctant to leave Sydney for the bush.

The College also had some powerful supporters fully aware of these reservations. To David Drummond as Minister, the College was a chance to establish a country college for country kids. The College was also intended as one key building block in the creation of the infrastructure required to support a Northern State. To S H Smith as head of the Department, the College was a chance to put his own ideas into practice.

Smith was then in his early sixties. Handsome and intelligent, with a commanding presence and a beautiful speaking voice, he was also shy, fussy, sensitive and vulnerable to personal attack.

Smith had started as a pupil teacher and then worked his way though the ranks, becoming Under-Secretary in 1922 upon the retirement of the famous Peter Board. Smith knew that there were those who affected to despise him because of his lack of formal education and was deeply wounded by it. Drummond was sensitive to Smith’s feelings and the two men became close.

Smith had clashed with Professor Alexander Mackie, the head of Sydney Teachers, College. Mackie, a brilliant Scottish-born academic, had come to Sydney in 1906 to head the newly established Sydney College. He was a man of strong views who believed that that the main emphasis in teacher training should be academic, that the independence of Sydney Teachers’ College must be preserved, and who had little time for financial or other constraints on his activities.

brilliant Scottish-born academic, had come to Sydney in 1906 to head the newly established Sydney College. He was a man of strong views who believed that that the main emphasis in teacher training should be academic, that the independence of Sydney Teachers’ College must be preserved, and who had little time for financial or other constraints on his activities.

Smith took a different view. Bound up in the day-to-day problems of State education, he regarded the College’s job as training those teachers the Department required in the way the Department required. Smith also disagreed with Mackie as to the most desirable form of teacher training: while not opposed to academic training, Smith thought that Mackie’s academic bias meant ill-trained teachers, and instead supported a more vocationally-oriented training.

These differences in approach would have made for difficulties anyway, but their personalities compounded problems. After Smith made a surprise inspection of Sydney Teachers’ College in 1927, Mackie wrote to him that such inspections could ‘only be done competently by a person with the necessary qualifications.’ He went on: ‘The inspection of highly qualified specialists on the College staff should be entrusted to men and women with similarly high academic qualifications and with extensive experience of College work.’ Not surprisingly, Smith found this letter ‘offensive’. For Smith’s part, he later commented sarcastically to Drummond that Mackie had ‘that type of mind which is usually associated with the Scottish metaphysician.’

The combination of committed Minister and Under-Secretary would have been irresistible in any case. However, they were joined by two other men.

A W Hicks, the very able local inspector who became a key Drummond aide and who would later occupy senior positions in the Education Department, took care of local logistics, while C B Newling as the College’s first Principal provided very strong leadership. Newling’s authoritarian style, his nickname was Pop, would not be acceptable today but was critical at the time.

Drummond, Smith, Hicks and Newling proved an irresistible combination.

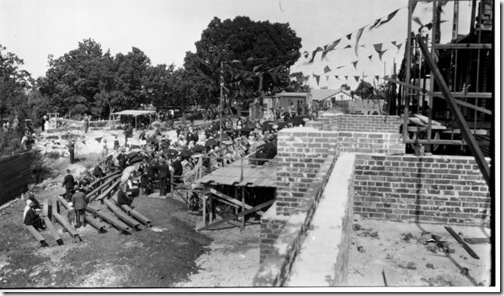

Note to readers: This post appeared as a column in the Armidale Express Extra on 24 July 2013. I am repeating the columns here with a lag because the columns are not on line outside subscription. You can see all the Belshaw World and History Revisited columns by clicking here for 2009, here for 2010, here for 2011, here for 2012, here for 2013. The photo shows the laying of the foundation stone for the new Teachers' Colle.