The fire ignited by Earle Page’s 17 February 1931 Glenreagh call for the people of the North to secede from New South Wales drew its strength in part from the now established desire for self-government for the North, more from the social and political tensions unleashed by the Great Depression.

At the outbreak of war in 1914, Australia’s population was just 4.9 million. During the war, 420,000 Australians enlisted, equivalent to 38.7 per cent of the male population. Some 60,000 died, others were wounded or became sick. Including deaths, wounded and sickness, the Australian casualty rate reached 64.8 per cent.

Many Australians returning from the front found readjustment to civilian life difficult. They provided a force for change that helped fuel many of the political movements including the rising Country Party and a resurgent Northern Separation Movement.

There were divisions on the right and left, fuelled in part by the rise of Bolshevism and the success of the Russian Revolution. The radicals looked to the possibility of change, the conservatives feared the overthrow of the existing order.

While the roaring twenties were nowhere near as prosperous as the label would suggest, economic growth was sufficient to contain the underlying divisions. However, that growth was patchy and built on unstable foundations.

Rising tariff protection encouraged expansion of manufacturing. In 1925-26 manufacturing employment exceed rural for the first time. Industrialisation was associated with and assisted by heavy expenditure on public works such as railways, electricity, roads and sewerage. The pattern of industrialisation and public works led to further growth in the metropolitan cities.

Metropolitan population growth became self-generating, for the need to house rising city populations added thousands more jobs in building and construction. Productivity growth in manufacturing was extremely low, import competition rising despite rising tariffs.

Industry responded by trying to control or even cut wages, which in turn led to continuing industrial trouble. Meantime, the rising drift of population to the city together with the cost squeeze placed upon primary export industries as a consequence of rising input costs began to fuel a new wave of country political agitation.

In 1929, the economic house of cards collapsed. The previous year new overseas borrowings to fund Government public works programs had reached fifty-two million pounds, while interest payments on accumulated loans had reached 28 per cent of export income.

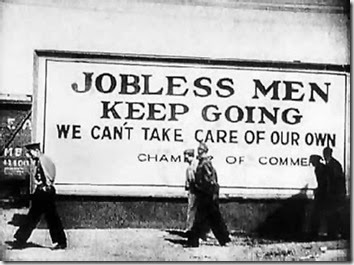

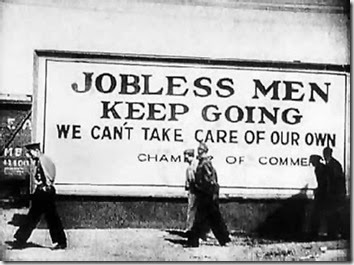

The perfect economic storm that now descended combined falling commodity prices with the closure of the London markets to new borrowings. Public works ground to a halt, while Governments were forced into a desperate search for solvency leading to Greek style expenditure cuts.

Unemployment rose and rose again, reaching 23.4 per cent by the end of 1930. As economic conditions worsened, previously submerged social and political tensions emerged. Australian society began to fragment.

Note to readers: This post appeared as a column in the Armidale Express Extra on 5 November 2014. I am repeating the columns here with a lag because they are not on line outside subscription. You can see all the Belshaw World and History Revisited columns by clicking here for 2009, here for 2010, here for 2011, here for 2012, here for 2013, here for 2014.

If you want to follow the story of the Northern or New England self-government movement, this is the entry post for the whole series